1. Introduction

Table of Contents

Did you know that besides the stray cats (Felis catus) that we commonly see in our neighbourhood, we have our very own native wild cat right here in Singapore?

With the extinction of the tiger (Panthera tigris) in the 1930s[1], the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) is Singapore's last wild cat, belonging to the family Felidae. Classified as critically endangered in the Singapore Red Data Book[2], the leopard cat is ironically considered a relatively common small cat in Asia[3]. Being elusive predators that are mainly active in the night[4], the leopard cat was thought to have disappeared from the Singapore mainland in 1968, with the first confirmed mainland record of a live leopard cat 43 years later[5]! Native to many Southeast Asian countries, the leopard cat has been facing several threats such as habitat loss and the global fur and pet trade[6] [see 5.3 Threats to Survival].

With many native species being lost over the years of deforestation and urbanization in Singapore[7], it is important for us to appreciate and learn more about our remaining local biodiversity. With heightened awareness, there will hopefully be a greater impetus to conserve our last surviving wild cat species.

This webpage aims to increase public knowledge in leopard cats by providing an interesting and comprehensive overview of its biology and conservation status. To facilitate understanding, difficult terms are hyper-linked to websites that explain the meaning of these terms. References are also indicated at the bottom of the page if you would like to access the original sources for more in-depth knowledge. So what are you waiting for? Read on to learn more about this charismatic species!

2. Species Identification

2.1 Morphology

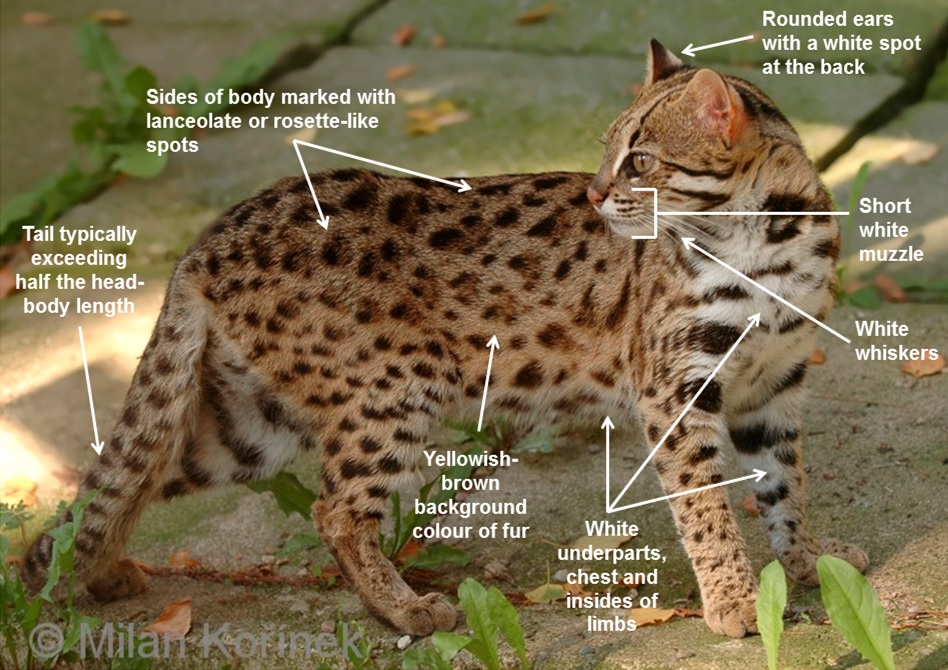

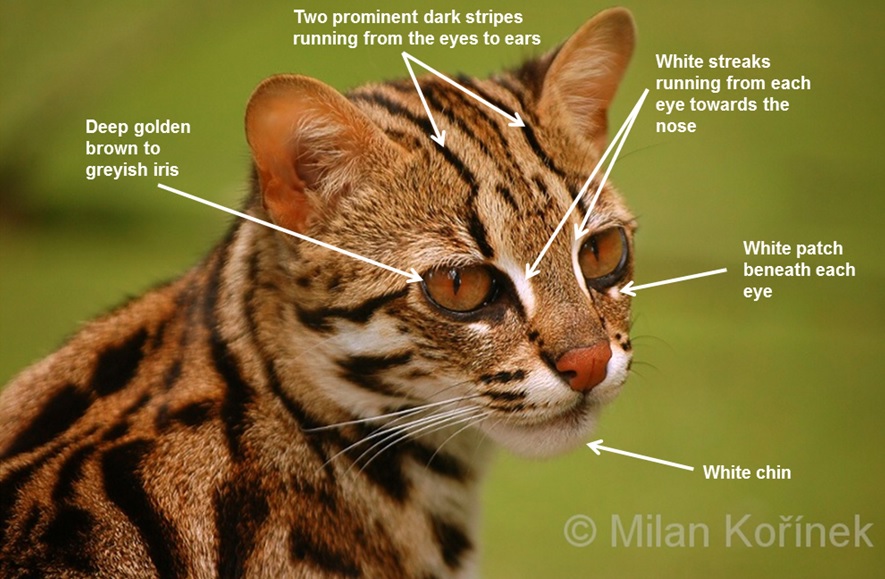

A leopard cat is about the size of a domestic cat (Felis catus), but with a more slender body[8]. Both sexes have similar physical appearances but the males are generally larger and heavier (3.3–4 kg) than females (2.5–3 kg)[9][10].The following figures are labelled with useful diagnostic features that you can take note of when identifying a leopard cat.

Here are some definitions that might come in handy when looking at the labelled photos.

Muzzle: Projecting part of the head of an animal, including jaws, mouth and nose

Rosette: Dark ring-shaped marks surrounding a patch of colour that is different from the background colour of the coat

Lanceolate: Narrow and tapering to a point at each end

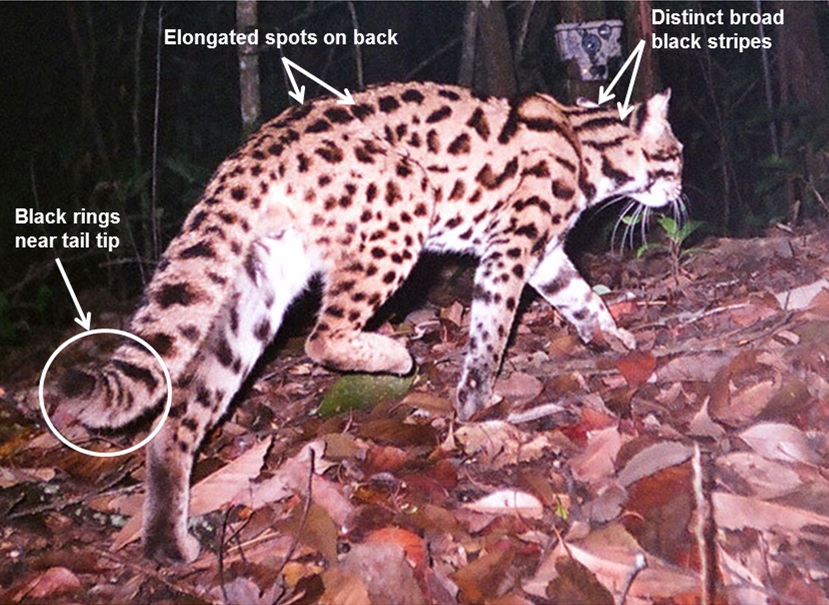

There are intra-specific variations in the coat length and coloration of leopard cats due to the different environmental conditions in different localities [see 3. Distribution]. At higher latitudes, they generally weigh more and have a longer and lighter coloured fur coat[15][16]. There are also several differences in skull morphology and body size among the different subspecies of leopard cats, for a more detailed description, please refer to[17]. In Southeast Asia, leopard cats weigh 1–5 kg and have a head to body length of 40–55 cm, with a tail measuring 23–29 cm, typically exceeding half the head to body length[18].Black spots of varying sizes dot the body, limbs and tail of the leopard cat. Its fur coat can also be recognized by four typically broad and distinct black stripes that run from the back of its head to its shoulders[19]. Two to four rows of elongated spots mark its back and its tail is often banded with black rings near the tip[20](see Figure 4 below).

Juvenile leopard cats also have similar physical appearances as the adults.

2.2 Confusion with Similar Wild Cat Species

With so many species of wild cats and their myriad forms of coat patterns, it is easy to confuse the leopard cat with other similar looking wild cats. Here is a brief summary table comparing the leopard cat and some similar species. Have a quick read on the distinct physical features highlighted and you may realise that they are not that similar after all!| Leopard Cat (P. bengalensis)(Kerr, 1792)Found in Asia and Eurasia [see 3. Distribution] |

Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) (Linnaeus, 1758)  |

Margay (Leopardus wiedii) (Schinz, 1821)  |

| Figure 6: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) in Zoo Olomouc, Czech Republic. Source: BioLib.cz (Photo by Milan Kořínek, used with permission) |

Figure 7: Captive L. pardalis in Beardsley Zoo, Connecticut. Source: Animal Diversity Web (Photo by James Dowling-Healey, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 License) |

Figure 8: L.wiedii. Source: EOL (Photo by Brian Gratwicke, Creative Commons BY 2.0 License) |

Back to top

3. Distribution

3.1 Global

The leopard cat has the widest distribution of any small felid and its range stretches from the Russian Far East, across China and Indo-china, to the west of India and even reaching high altitudes in the Himalayas[29]. The interactive map below illustrates the global distribution of the leopard cat. Do click the place markers to check out the locations for each subspecies of leopard cat (markers of the same colour represent one specific subspecies)! A more detailed table for the leopard cat's range is listed below as well.| Name of Subspecies |

Range |

| P. b. alleni Sody, 1949 |

Hainan Island[30] |

| P. b. bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) |

India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Indo-china and Yunnan in China[31] |

| P. b. borneoensis Brongersma, 1936 |

Borneo[32] |

| P. b. chinensis (Gray, 1837) |

Taiwan and China except Yunnan[33] |

| P. b. euptilurus (Elliott, 1871) |

Northeastern Eurasian continent, Korean Peninsula, Tsushima Islands in Japan[34] |

| P. b. heaneyi Groves, 1997 |

Palawan island in the Philippines[35] |

| P. b. horsfieldi (Gray, 1842) |

Kashmir, Punjab, Kumaon, Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim[36] |

| P. b iriomotensis (Imaizumi, 1967) |

Iriomote Islands in Japan[37][38] |

| P. b. javanensis (Desmarest, 1816) |

Java, Bali[39] |

| P. b. rabori Groves, 1997 |

Negros, Panay and Cebu islands in the Philippines[40] |

| P. b. sumatranus (Horsfield, 1821) |

Sumatra and offshore island of Tebingtinggi[41] |

| P. b. trevelyani (Pocock, 1939) |

Northern Kashmir, upper Punjab and Southern Baluchistan[42] |

3.2 Local (Singapore)

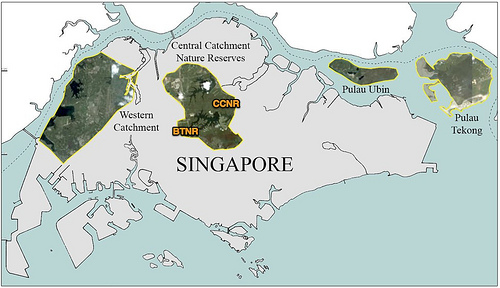

In Singapore, the leopard cat (P. b. bengalensis) is known to be present on the remaining major forest fragments: on the offshore islands of Pulau Ubin and Pulau Tekong, and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR)[43] and Western Catchment area on the mainland[44].

Back to top

4. Biology

4.1 Lifespan

Leopard cats have an average lifespan of about 4 years in the wild[45]. In captivity, they have been known to live for more than 15 years[46].4.2 Habitat

Leopard cats can be found in a wide range of habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate forests and even mountainous areas of up to 3000 m in the Himalayas[47][48]. They are also rather resistant to human disturbance as compared to other Asian wild cats[49]and are known to survive well in modified landscapes such as logged forests, agricultural fields and oil palm plantations[50][51]. Leopard cats usually live in proximity to water sources as well[52].

Leopard cats can be found in a wide range of habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate forests and even mountainous areas of up to 3000 m in the Himalayas[47][48]. They are also rather resistant to human disturbance as compared to other Asian wild cats[49]and are known to survive well in modified landscapes such as logged forests, agricultural fields and oil palm plantations[50][51]. Leopard cats usually live in proximity to water sources as well[52].Figure 10: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) in an oil palm plantation. Source: Cat Specialist Group (Photo by J. Ross & A. Hearn, permission pending)

4.3 Home Range

The home range of leopard cats ranges from 2 km2 to over 10 km2 but generally falls between 2.5 km2 to 5.4 km2[53][54][55]. Some studies have shown similar range sizes for both male and female leopard cats[56][57]. The size of home ranges are usually constrained by the area of suitable habitat and the degree of resource competition[58].4.4 Diet

Leopard cats are primarily carnivorous and prey on terrestrial vertebrates such as rodents, insects, reptiles and sometimes even birds such as the Red Junglefowl[59]! As rodents typically form the largest proportion of terrestrial small-mammal communities in tropical rainforests[60], they make up the main bulk of the leopard cats' prey in many parts of the cats' geographical range[61][62][63][64][65]. However, food habits may vary seasonally due to prey availability for leopard cats living in sub-tropical climates. For example, the Iriomote leopard cat (P. b. iriomotensis) selectively preys on skinks (a type of lizard) during the warm season when skinks are more abundant[66].Figure 11: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) carrying a rodent. Source: Cat Specialist Group (Photo by J. Ross & A. Hearn, permission pending)

Figure 12: Left: Lateral view of leopard cat (P.bengalensis) skull; Right: Lower tooth row of leopard cat (P.bengalensis), both specimens from the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 161319, specimen from Philippines, Negros Oriental. Source: Animal Diversity Web (Photo by Phil Myers, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0. Annotations by Lee Jia Yi, with reference to the "Dental Anatomy of Cats")

With relatively smaller canines, narrower muzzles and slightly longer jaws as compared to larger felids, small prey specialists like leopard cats gain the advantage of speed when catching small quick-moving prey[67]. Like other felids, leopard cats also have specialized dentition that is adapted for a carnivorous diet (see Figure 12 above). Canines are used for seizing and puncturing prey with minimal force. Incisors are used to pluck fur and feathers from the prey prior to feeding, and pulling flesh away from the carcass during feeding. Leopard cats also have well-developed upper and lower carnassials that fit together and shear flesh in a scissor-like motion[68].

4.4.1 Ecological Role

On islands far away from the mainland, leopard cats are usually the only carnivorous species present and play an important role of being one of the top predators[69]. Following the extinction of large vertebrates in Singapore due to habitat loss[70], the leopard cat is also likely to be one of the top predators in Singapore’s terrestrial ecosystem. Thus, the leopard cat may play an integral role in controlling small mammal and reptile communities and maintaining the trophic structures of food webs. Their preference for rodent prey has also made them a good candidate as a form of biological rodent control in areas such as oil palm plantations where rodents are considered to be pests[71].4.5 Locomotion

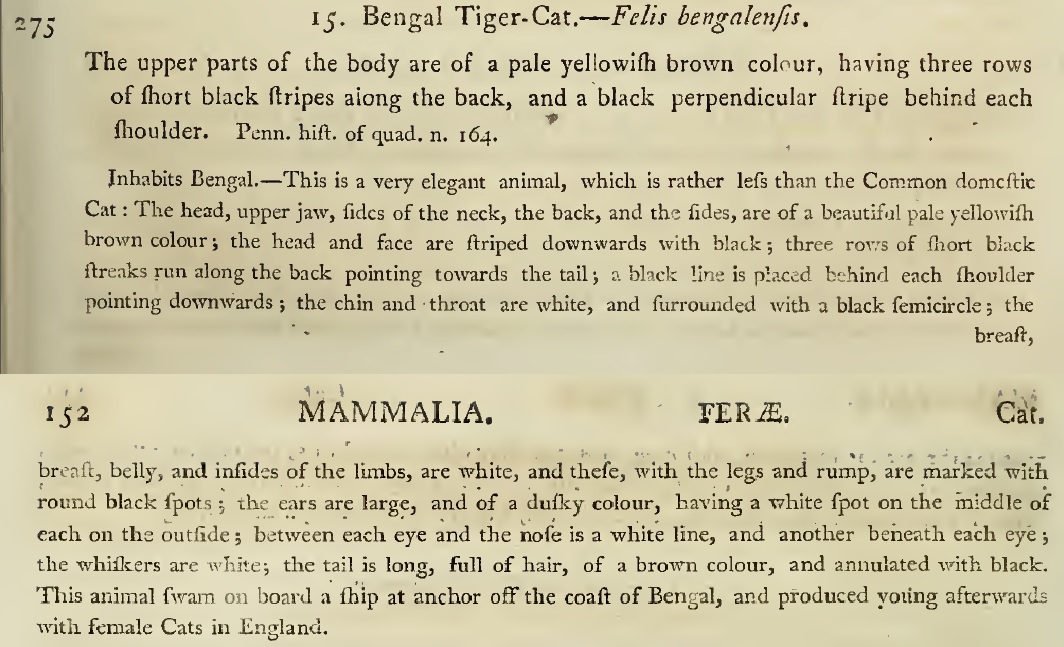

Although leopard cats are primarily ground-dwelling, they are arboreal to some extent and have been reported to rest in trees high in the canopy[72][73]. Their long tails [see 2.1 Morphology] are able to provide them with balance while climbing and leaping among branches at heights[74].Leopard cats are also known to be excellent swimmers and the type specimen was said to have swam on board a ship in the Bay of Bengal [see 6.2 Original Description][75]. Their swimming ability has likely contributed to their successful colonization of offshore islands such as Tsushima Island and Iriomote Island[76].

Figure 13: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) on a tree swamp about 1 m above ground,

Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Nee Soon swamp-forest, Singapore.

Source: Singapore Biodiversity Records 2015 (Photo by Marcus Chua, used with permission)

Back to top

4.6 Communication

4.6.1 Acoustic

Vocalization is an important aspect of intra-specific communication of felids. The leopard cat can produce a friendly close-range sound called a ‘gurgle’. It is a short coherent pulsed sound which can be uttered by females and males in close-contact situations such as courtship and mating, and also by females towards their offspring. Gurgles may be vocalized when the leopard cat is in any posture and also during locomotion[77].4.6.2 Olfactory

Like most felids, leopard cats are highly dependent on olfactory communication. They use scat (faeces) and urine to communicate with one another by scent marking their territories[78]. Through these scent markings, leopard cats are able to recognize individuals of different sexes and even detect their reproductive status[79]!

Like most felids, leopard cats are highly dependent on olfactory communication. They use scat (faeces) and urine to communicate with one another by scent marking their territories[78]. Through these scent markings, leopard cats are able to recognize individuals of different sexes and even detect their reproductive status[79]!Figure 14: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) scent marking. Source: Cat Specialist Group (Photo by J. Ross, permission pending)

4.7 Behaviour

4.7.1 Foraging

Leopard cats are ambush predators that usually hide in wait and stalk their prey by crouching low to the ground, before attacking by surprise[80]. They generally rely on sight and sound to hunt[81].4.7.2 Activity Pattern

Leopard cats are generally considered to be nocturnal animals[82], but radio telemetry and camera-trapping studies in Southeast Asia have revealed that they can be frequently active during the day[83][84].Such an activity pattern has been found to be correlated with the activity pattern of their main prey[85], which are usually nocturnal rodents [see 4.4 Diet] This synchronization is beneficial as the leopard cat seems to be adapted to actively hunt when prey encounter rates are higher[86]. Forms of activity observed during studies ranged from grooming to locomotion. Click here to watch a short clip of a leopard cat grooming itself in the wild!

Due to the lack of quality videos on wild leopard cats, let's take a look at a video of a captive cat in action in the Singapore Zoo (resting, locomotion and feeding activity observed)!

Figure 15: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) at an oil palm plantation adjacent to primary lowland forest at Merapoh, Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia. Source: Ecology Asia (Photo by Nick Baker, used with permission)

Video 1: Singapore Zoo - Leopard Cat (P. bengalensis). Credit: rendezvous009

4.8 Reproduction

Not much is known about the mating system of leopard cats but they are thought to be polygynous. The breeding season varies according to the local climate, with leopard cats mating year-round in the tropics while in colder habitats up north, kittens are born only once a year in spring[87]. Gestation lasts about 62 to 75 days and females can give birth to about 1– 4 kittens per litter. The average age at reproductive maturity for both sexes is 18 months. Females are the primary caregivers and look after their offspring for about 8 months until the kittens are independent[88].

Not much is known about the mating system of leopard cats but they are thought to be polygynous. The breeding season varies according to the local climate, with leopard cats mating year-round in the tropics while in colder habitats up north, kittens are born only once a year in spring[87]. Gestation lasts about 62 to 75 days and females can give birth to about 1– 4 kittens per litter. The average age at reproductive maturity for both sexes is 18 months. Females are the primary caregivers and look after their offspring for about 8 months until the kittens are independent[88].Figure 16: Visayan leopard cat (P.b. rabori) kittens at Tierpark Berlin, Germany, 2014. Source: Zooborns

4.9 Additional Fun Facts

a. Did you know that leopard cats are solitary except during the breeding season[89]?b. The coat pattern of the leopard cat is likely to function as disruptive colouration, which is a form of camouflage that can prevent the cat from being seen when it is stalking prey[90]. The coat pattern can also be a defensive adaptation, concealing the leopard cat from its predators[91].

Back to top

5. Conservation

5.1 Global Conservation Status

The leopard cat is categorised under the "Least Concern" status by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, a comprehensive global list of taxonomic, conservation status and distribution information for organisms. It is classified as such due to its wide range and stable population size in many areas, with some reportedly surviving well in human-modified habitats such as agricultural plantations[92]. However, some island populations are at a higher risk of extinction. The Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis) on Iriomote Island is listed as "Critically Endangered" on the IUCN Red List due to a declining population with an estimated size of less than 250 mature individuals[93]. The Visayan leopard cat (P. b. rabori) of the Philippine islands of Panay, Negros and Cebu is listed as "Vulnerable", mainly due to habitat loss resulting in a declining population[94].5.2 Local (Singapore) Conservation Status

In Singapore, the leopard cat is currently listed as "Critically Endangered" (less than 250 mature individuals)[95] in the Singapore Red Data Book[96], a list of threatened species in Singapore. Largely due to a decline in habitat quality on the mainland, the conservation status of the leopard cat was shifted to higher conservation priority from its "Endangered" status assigned in 1994[97]. With a potentially important role in the ecosystem [see 4.4.1 Ecological Role], there is indeed an urgent need for comprehensive conservation plans to ensure the long-term survival of the leopard cat.Figure 17: Singapore Red Data Book, Second Edition. Source: LKCNHM eBooksBack to top

5.3 Threats to Survival and Conservation Efforts

5.3.1 Commercial Trade

a. Fur TradeOne of the major threats to the survival of leopard cats is the global demand for leopard cat fur coats. In the 1980s, leopard cats were heavily exploited in China, with hundreds of thousands of stockpiles and exports of skins. Europe was formerly a primary destination for the exports of leopard cat coats but after an import ban in 1988, Japan became the main importer. There is also substantial demand for leopard cat coats in China[98]. Even in the 2000s, the leopard cat is still widely traded for their fur in countries such as Myanmar, China, Thailand and Pakistan[99][100].

Surveys conducted by TRAFFIC, the leading global wildlife trade monitoring network, have discovered that leopard cat skins are the most commonly sold wild cat species in Myanmar wildlife markets (see Figure 18 below), a country where it is not protected under national law. Majority of the wild cat parts sold in such markets are sold to international buyers[101].

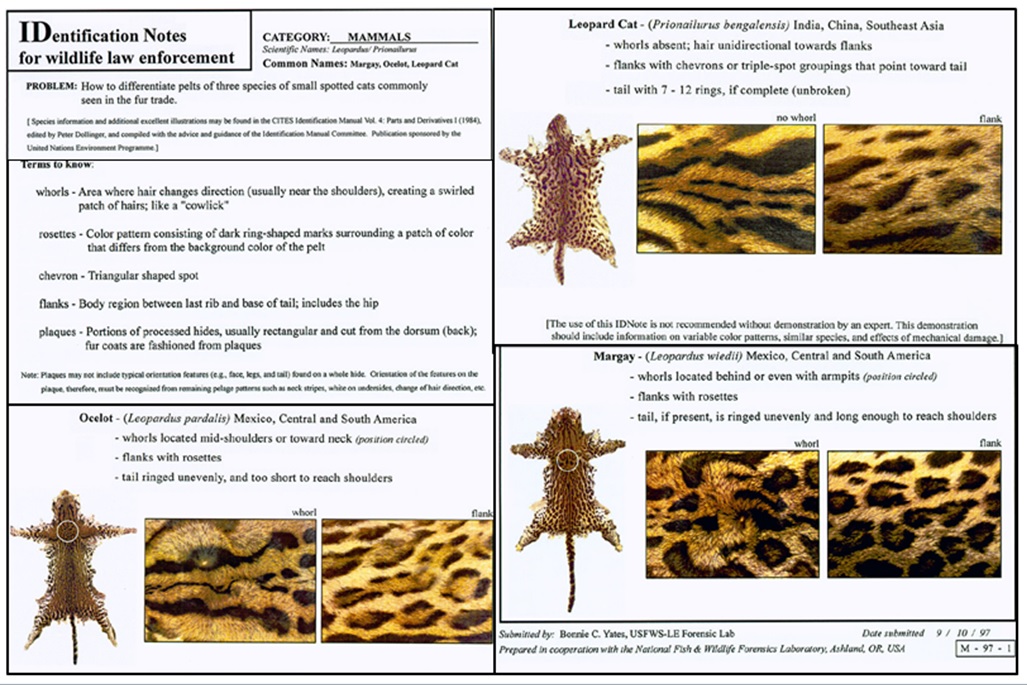

Many wild cat species are highly coveted for their beautifully patterned coats and with leopard cat coats being very similar to those of other small wild cats (such as the ocelot and margay [see 2.2 Confusion with Similar Wild Cat Species]), special identification guidelines have even been developed to aid wildlife law enforcement officials in differentiating coats for monitoring purposes.

Figure 19: Identification notes for ocelot, margay and leopard cat coats. Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

b. Pet Trade

Leopard cats are also occasionally kept as pets. Artificial hybridisation with the domestic cat (Felis catus) has resulted in a highly prized breed of pet cats known as the Bengal cat[102]. Although hybridisation with feral domestic cats has been reported in the wild, it is not considered a significant threat yet[103][104]. However, breeding a leopard cat with a domestic cat leads to fewer chances of leopard cat genes being passed on to future generations due to fewer pure leopard cat offspring produced. Furthermore, the demand for Bengal cats puts pressure on leopard cat populations in the wild as breeders continue to source for suitable hybridisation candidates. If the breeding of Bengal cats is not properly controlled, wild leopard cat populations could decline and there may be problems of inbreeding within small populations[105]. Inbreeding reduces the genetic variation of populations and may pose serious problems as deleterious mutations accumulate. Population fitness can be reduced, threatening the long-term survival of the species concerned[106].

In America, there numerous incidents of pet owners abandoning their Bengal cats as they are unable to handle their wild temperament. This issue is even affecting some wildlife rescue shelters which are already facing space constraints in their facilities[107]! With so many cascading consequences of acquiring a Bengal cat, please do think twice if you intend to purchase any kind of exotic hybrid pets. Click here to read about the heartbreaking stories of Bengal cats and other hybrid cats being abandoned.

c. Conservation EffortThe leopard cat is protected under the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), an inter-governmental agreement that aims to ensure that wildlife trade does not threaten the survival of wild species. The populations of P. b. bengalensis in India, Bangladesh and Thailand are listed under Appendix I, which involves the prohibition of international trade of the species concerned, except for non-commercial purposes. All other populations of leopard cats are listed under Appendix II, which includes species that require tight trade control although they might not be currently threatened. International trade of specimens of Appendix II species is permitted with the authorization of relevant export licenses[108][109].

In Singapore, leopard cats are protected by law under the Wild Animals and Birds Act. Under the Act, it is an offence for any person who: kills/takes/keeps any leopard cat without a license or sells/imports/exports any leopard cat that is illegally acquired[110]. Although international trade regulations such as CITES have been implemented to protect the leopard cat, cross-border trading of leopard cat parts in Myanmar, China and Thailand (all three countries are signatories to CITES[111]) [see a. Fur Trade] reflects a serious lack of legislative enforcement to prevent illegal wildlife trade. There is thus an urgent need for international cooperation in wildlife law enforcement to crack down on the illegal trade of leopard cats. Further monitoring of the trade is also needed to better assess the conservation status of the leopard cat. Threatened populations of leopard cats such as the Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis) on Iriomote Island, Visayan cat (P. b. rabori) of the Philippine islands [see 5.1 Global Conservation Status] and the Tsushima cat (P. b. euptilurus) of the Tsushima Islands[112] should be included in Appendix I of CITES as well.

5.3.2 Habitat Loss

Although leopard cats are less dependent on forest cover as compared to other wild cats[113], habitat loss remains a major threat across most of its geographical range[114][115]. Habitat loss often stems from economic development and one of the imminent threats to the critically endangered Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis) is the development of Iriomote Island as a tourist attraction, as well as ongoing agricultural projects on the island[116]. Habitat destruction can bring leopard cats closer to human settlements and increase the risk of human-wildlife conflict. Habitat loss can also be in the form of habitat fragmentation, breaking up previously connecting habitats and further isolating populations.

The following sections are categorized as the different threats to the leopard cat, all stemming from the issue of habitat loss. Specific conservation efforts are also grouped under each form of threat.

a) Human-Wildlife ConflictAs the rate of deforestation accelerates, highly suitable habitats for leopard cats can be located in close proximity to rural settlements. Those that live in such areas are often viewed as poultry pests and can face deadly attacks by villagers in retaliation for killing their poultry[117][118].

ai) Conservation EffortsThe video below illustrates a conservation effort in Miaoli County, Taiwan, that is aimed to balance the needs of both farmers and leopard cats to prevent any form of conflict. Conservationists educate the farmers on the importance of leopard cats and implement the idea of "Leopard Cat Rice". This "special" rice is cultivated in eco-friendly practices that help sustain healthy rodent populations as food sources for the leopard cats.

Video 2: Conservationist balances needs of farmers and endangered leopard cats. Credit: Formosa EnglishNews

b) Habitat Fragmentation

Due to the lack of ecological connectivity between fragmented habitats, leopard cats have been taking to the roads in search of suitable habitats[119].

Due to the lack of ecological connectivity between fragmented habitats, leopard cats have been taking to the roads in search of suitable habitats[119].In urbanized Singapore, we can see the effects of habitat fragmentation on leopard cats in the form of road-kills (see Figure 20). In 2015, two leopard cat deaths have already been reported, one at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve and the other near a condominium at Bukit Timah[120][121]. Although they are unlikely to be road-kills, they were found in relatively exposed areas away from their natural habitat, possibly searching for suitable habitats.

Figure 20: 2001 Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) road-kill found at Mandai Road Exit, Bukit Timah Expressway, Singapore.(Photo by Charidth Pelpola, used with permission)

Figure 21: Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) carcass found in Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve, 9 June 2015. Source: Facebook (Photo by LKCNHM)

In Singapore, leopard cat carcasses are collected and preserved at the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Musuem (LKCNHM) for further studies. Each carcass is a valuable record that provides important clues about different aspects of an individual's biology such as its age, molecular information and even its last meal! If you see a dead animal, please kindly notify LKCNHM by calling them at 6516 5082 or alternatively contacting them via this link.

Unfortunately, the problem of leopard cats attempting to cross roads is not only confined to Singapore. In Malaysia, there have also been frequent reports of leopard cats being killed in traffic accidents[122]. Road-kills are also a critical factor affecting leopard cat populations on Iriomote Island and Tsushima Island in Japan[123].

bi) Conservation Efforts On Iriomote Island, specific measures have been implemented to prevent leopard cat road-kills based on data such as the location and season of accident occurrences. Underpasses were constructed for leopard cats and camera traps were installed to monitor the usage of the passes. Road signs were also put up to warn drivers of wildlife crossings and special structures were built to reduce the driving speeds of vehicles at specific locations. Publicity campaigns were also rolled out to engage drivers. Camera-trap monitoring programs are also in place on Iriomote and Tsushima Island, collecting important sighting records that help scientists understand more about the structure of the leopard cat population[124]. Captive breeding programs are also being developed for leopard cat populations on Tsushima and Negros islands[125].

5.3.3 Undesirable Inter-specific Interactions

For the threatened leopard cat populations on Iriomote and Tsushima islands, they are plagued with additional threats due to undesirable interactions with other species. More research is required in other countries to find out whether other leopard cat populations are at risk of such threats as well.ai) Introduced DiseasesOne of the most serious threats that may wipe out small isolated populations is the potential for disease transmission from domestic cats (Felis catus) to leopard cats[126]. Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), a deadly virus attacking the cat immune system, has been reportedly transmitted from domestic cats to the Tsushima cat (P. b. euptilurus)[127].

aii) PredationThe Tsushima cat (P. b. euptilurus) also faces the threat of predation by domestic dogs (Canis lupus). Wild boars (Sus scrofa) are also a potential predator on leopard cat kittens[128][129].

aiii) Inter-specific CompetitionThe Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis) is at risk of resource competition from introduced feral cats (Felis catus) due to a resource overlap for habitat and prey between both animals[130]. On Tsushima Island, there is also a similar concern of inter-competition with domestic cats (Felis catus), which are commonly cared for by people living on the island. These domestic cats roam freely and they are known to eat the same prey as the native leopard cats. The growing wild boar (Sus scrofa) population on Tsushima Island may also influence prey availability to the leopard cats[131].

b) Conservation EffortsAs feral and free-ranging house cats are potential disease carriers and resource competitors, measures have been implemented to reduce the numbers of these cats on both Iriomote and Tsushima islands. On Iriomote Island, feral cats were trapped and transported out of the island for potential adoption. On Tsushima Island, educational campaigns were carried out for cat owners, highlighting the need for breeding control and vaccination. However, success in decreasing the feral cat population has been lower on Tsushima Island due to the larger land area and greater abundance of feral and house cats. Camera trap programs mentioned earlier are also important in monitoring the interactions between leopard cats and other species[132].

Back to top

6. Taxonomy and Systematics

The terms taxonomy and systematics may be foreign to the layman, but respectively in short, they mean the science of grouping organisms and the study of evolutionary relationships among organisms.

Accurate taxonomic classification schemes and systematic information are essential in mapping out felid diversity [see 6.4 Phylogeny] and establishing adequate conservation management plans[133]. For example, if the Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis) is classified as a full species, it will be recognized as the most endangered cat in the world and is likely to warrant higher priority in conservation action plans. Since it is currently recognized as a subspecies[134], it becomes one of the many island populations of a common cat species in Tropical Asia and therefore might be of relatively less global conservation concern.

A hierarchical summary of the taxonomic classification of the leopard cat is presented as follows[135]:

Animalia Chordata Mammalia Carnivora Felidae Prionailurus Prionailurus bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) P. b. alleni Sody, 1949 P. b. bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) P. b. borneoensis Brongersma, 1936 P. b. chinensis (Gray, 1837) P. b. euptilurus (Elliott, 1871) P. b. heaneyi Groves, 1997 P. b. horsfieldi (Gray, 1842) P. b iriomotensis (Imaizumi, 1967) P. b. javanensis (Desmarest, 1816) P. b. rabori Groves, 1997 P. b. sumatranus (Horsfield, 1821) P. b. trevelyani (Pocock, 1939)

The leopard cat was first described by Robert Kerr in 1792 under the scientific name Felis bengalensis [see 6.2 Original Description]. Between 1829 and 1922, there were many more descriptions that classified the leopard cat under both the Felis and Leopardus genera[136]. In 1858, a Russian naturalist Nikolai Severtzov proposed the genus name Prionailurus[137] and in 1917, the British zoologist Reginald Innes Pocock officially recognized the taxonomic classification of Prionailurus, describing the genus based on its unique skin and skull morphological characteristics[138]. Subsequently, Pocock classified the leopard cat (P. bengalensis), rusty spotted cat (P. rubiginosus) and the fishing cat (P. viverrinus) under the genus Prionailurus[139]. Back to top

6.1 Nomenclature

Binomial/Scientific Name: Prionailurus bengalensis (Kerr, 1792) Vernacular/Common Name: Leopard cat, 豹猫, Kucing batu[140] (for more examples of common names click here and search under the "Description" tab)In the binomial/scientific name of the leopard cat, “(Kerr, 1792)” is usually included, with “Kerr” being the name of the author who originally described the leopard cat and “1792” being the year of the original description. The author name and date is put in brackets when the species is re-classified under a different genus from the one in which it was originally described[141].

Synonyms: alleni Sody, 1949; anastasiae (Satunin, 1905); anguliferus Fitzinger, 1868; borneoensis Brongersma, 1936; chinensis (Gray, 1837); decoloratus (Milne-Edwards, 1872); ellioti (Gray, 1842); euptilurus (Elliot, 1871); Felis bengalensis Kerr, 1792; hainanus Xu and Liu, 1983; heaneyi Groves, 1997; herschelii (Gray, 1869); horsfieldii (Gray, 1842); ingrami (Bonhote, 1903); javanensis Desmarest, 1816; javensis Elliot, 1882; jerdoni Blyth, 1863; manchuricus (Mori, 1922); microtis (Milne-Edwards, 1872); minutus (Temminck, 1824) [preoccupied]; nipalensis (Horsfield and Vigors, 1829); nipalensis (Hodgson, 1832) [preoccupied]; pardochrous (Hodgson, 1844); rabori Groves, 1997; raddei (Trouessart, 1904); reevesii (Gray, 1843); ricketti (Bonhote, 1903); scriptus (Milne-Edwards, 1870); servalinus Gray, 1843; sinensis (Shih, 1930); sumatranus Horsfield, 1821; tenasserimensis (Gray, 1867); tingius Lyon, 1908; trevelyani Pocock, 1939; undatus Desmarest, 1816; undatus (Radde, 1862); wagati (Gray, 1867)[142].

Although the concept of subspecies remains subjective[143], the broad geographical distribution of the leopard cat has led to the current classification of 12 subspecies[144] [see 3. Distribution] based on variations in morphology and genetics[145].

Names of Subspecies:

- P. b. alleni Sody, 1949

- P. b. bengalensis (Kerr, 1792)

- P. b. borneoensis Brongersma, 1936

- P. b. chinensis (Gray, 1837)

- P. b. euptilurus (Elliott, 1871)

- P. b. heaneyi Groves, 1997

- P. b. horsfieldi (Gray, 1842)

- P. b iriomotensis (Imaizumi, 1967)

- P. b. javanensis (Desmarest, 1816)

- P. b. rabori Groves, 1997

- P. b. sumatranus (Horsfield, 1821)

- P. b. trevelyani (Pocock, 1939)

Figure 22: Clockwise from left: P. b. euptilurus in Zoo Olomouc, Czech Republic. Source: BioLib.cz (Photo by Milan Kořínek, used with permission); P. b. heaneyi in Tierpark Berlin, Germany. Source: BioLib.cz (Photo by Klaus Rudloff, used with permission); P. b. borneoensis in Miri Crocodile Farm, Sarawak, Malaysia. Source: EOL (Photo by Bernard Dupont, Creative Commons BY-SA 2.0 License)

6.1.1 Etymology

The generic epithet Prionailurus, is derived from the Greek words "prion" (saw) and "ailurus" (cat)[146]. The specific epithet bengalensis as its name suggests, refers to the Bengal region in the Indian subcontinent where Robert Kerr first described the leopard cat [see 6.2 Original Description below].Back to top

6.2 Original Description

The leopard cat was originally described by Robert Kerr in 1792 under the name Felis bengalensis[147]. His description was published in his translation of one of Carl Linnaeus's major works: The animal kingdom, or zoological system, of the celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus. This description was based on a specimen that swam on board a ship off the coast of Bengal[148].

6.3 Type Information

The type specimen for the leopard cat is the specimen to which the organism was originally described, which in this case is the leopard cat described by Robert Kerr [see 6.2 Original Description]. Type specimens are usually kept in museum research collections to facilitate easy access for scientific examination. Unfortunately, the location for the type specimen of the leopard cat is unknown.Back to top

6.4 Phylogeny

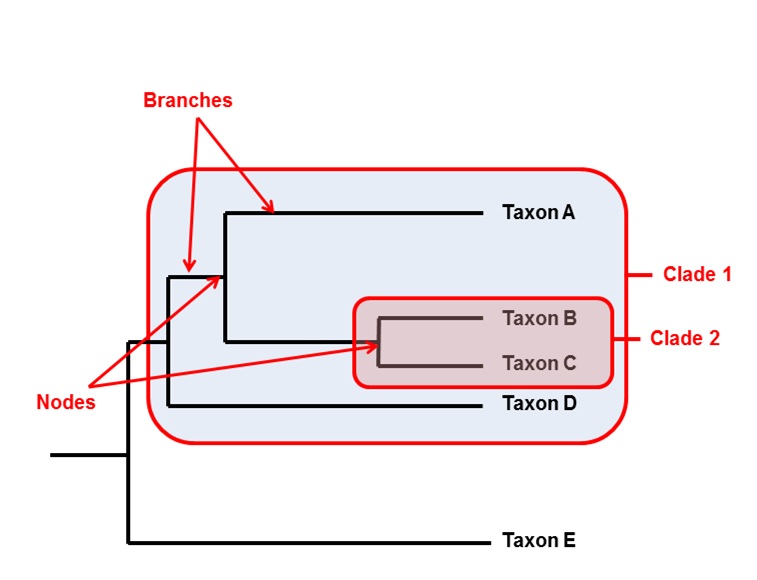

The study of taxonomy and systematics are applied in the construction of phylogenetic trees, which are diagrams depicting inferred evolutionary relationships among organisms. Phylogenetic trees are constructed by comparing various characteristics among organisms. Such characteristics are usually in the form of molecular or morphological information and suitable characters are those known to be derived and shared among groups of organisms[149].Before we go into the details of the phylogeny of the leopard cat, let’s take a look at a short guide on how to interpret phylogenetic trees!

Figure 24: Basic structure of a phylogenetic tree (Image by Lee Jia Yi, with reference to Dave Hone's blog)

Figure 24 shows a basic structure of a phylogenetic tree, with the alphabets representing taxons, which are specific biological groupings of organisms. The branches of the tree trace the pathways of hypothesized evolutionary histories of the different lineages. A clade is a group of organisms that consists of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. The points at which the branches diverge are called nodes, which represent the hypothetical ancestors of the descendants. In the example tree in Figure 24, we can see that Taxon E was the first to evolve as the ancestors of that taxon were the first to branch off.

To begin, we look at the broader picture of the phylogeny of the family Felidae, to which the leopard cat belongs. Due to copyright issues, the phylogenetic tree from Werdelin et al.(2010) cannot be reproduced on this webpage and it will be useful to refer to Figure 2.1 in the original source[150] to complement the following description. Figure 2.1 depicts a phylogenetic tree constructed based on DNA sequences. The study distinguishes eight clades of extant felids which have evolved from a common ancestor about 11 million years ago (see Node A, Figure 2.1 in original source). The eight clades are: the Panthera lineage (genera Neofelis and Panthera), the bay cat lineage (genus Pardofelis), the Caracal lineage (genera Caracal and Leptailurus), the ocelot lineage (genus Leopardus), the lynx lineage (genus Lynx), the puma lineage (genera Puma and Acinonyx), the leopard cat lineage (genera Otocolobus and Prionailurus) and the domestic cat lineage (genus Felis) (named in chronological order of splitting from the common ancestor of the eight clades).The leopard cat and domestic cat lineages split from each other approximately 6.2 million years ago (refer to Node G, Figure 2.1 in original source). Although the common name “leopard cat” consists of the word “leopard”, we can see from the phylogenetic tree that the leopard cat is actually more closely related to species in the lynx and puma lineages as compared to those in the genus Leopardus, or the famous species Panthera pardus, more commonly known as the leopard[151].

Apart from molecular information, studies have also used morphological characters such as coat patterns and pupil shape to reconstruct the phylogeny of felids[152]. ‘Non-traditional’ characters such as behavioural and even chemical characters are being used to build phylogenetic trees as well. Such characters often come into handy in resolving incongruent phylogenetic information based on molecular and morphological data. A phylogenetic analysis taking into account various characters is likely to yield a more holistic view of evolutionary relationships[153].

An interesting phylogenetic study by Bininda-emonds et al. (2001) analysed biochemical (lipid) compounds in the scent glands of 16 felid species including the leopard cat (refer to Figure 2 in original source[154]). As chemical secretions commonly serve as a mode of intra-specific communication for felids [see 4.6.2 Olfactory], they can be useful for phylogenetic analysis, giving us clues about the evolution of communication among felids[155].

In some cases, molecular comparisons during phylogenetic tree construction have revealed close similarities between species previously described as distinct from each other. This may lead scientists to revoke the full species status of some organisms and re-classify them under a subspecies status instead[156]. This was the case for one of the leopard cat subspecies, the Iriomote cat (P. b. iriomotensis), which is only found in the small island of Iriomote in Japan[157]. The Iriomote cat was originally described as a monotypic genus based on morphology and named Mayailurus iriomotensis[158]. However, after phylogenetic tree construction based on DNA sequences, the Iriomote cat was revealed to be closely related to the continental leopard cats, thus relegating them to a subspecies status that is currently internationally recognized[159][160].

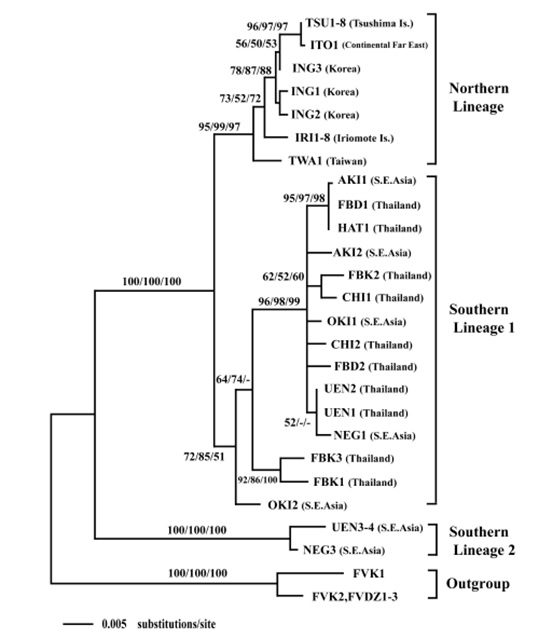

Taking a closer look on the species level, studies have investigated the genetic diversity and phylogeography of the leopard cat. Tamada et al. (2008) constructed phylogenetic trees from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences for 39 leopard cats from different localities[161].

From Figure 25, we can see that there are three clades on the tree, a Northern lineage consisting of leopard cats from northern Asia (Tsushima Islands, continental Far East, Korean Peninsula, Iriomote Island and Taiwan), and two clades termed Southern Lineage 1 and Southern Lineage 2 comprising Southeast Asian leopard cats. Southern Lineage 1 revealed higher genetic diversity and was more closely related to the Northern Lineage as compared to Southern Lineage 2. Genetic differentiation among the northern populations likely reflects past geographical isolation from the continental populations[163].

Through such phylogenetic analyses, we can understand more about the genetic diversities of isolated and endangered leopard cat populations such as those on Tsushima Island, Iriomote Island and Singapore as well. Such knowledge will be critical for conservation efforts in light of growing concerns of increasingly isolated wild populations and potential inbreeding effects[164].

Back to top

7. Useful Links

- A blog by a leopard cat researcher in Singapore:

- Leopard cat (P. bengalensis) on the IUCN Red List

- For more information about the leopard cat and other wild cats, you can visit the websites of ISEC Canada and the Cat Specialist Group!

Figure 26: Leopard cat (P. b. bengalensis). Source: Animalia(Photo by M Kuhn, Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 2.0 License)

Back to top

8. References

Disclaimer: Due to the limited referencing function of Wikispaces, many references are repeated in order to facilitate easy navigation back up to the respective in-text citations. Formatting issues may also be observed due to technical incompatabilities.(Last updated: 1 January 2016).

National Library Board. (2004). "Tigers in Singapore", Singapore Infopedia: http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_1081_2007-01-17.html (accessed 9 November 2015).

Chua, A.H.M., Sivasothi, N & Ng, P.K.L. (2015). "Leopard cat in Central Catchment Nature Reserve" Singapore Biodiversity Records 2015:

http://lkcnhm.nus.edu.sg/nus/index.php/sbr/sbr15 (accessed 11 November 2015).

Sanderson, J., Sunarto, S., Wilting, A., Driscoll, C., Lorica, R., Ross, J., Hearn, A., Mujkherjee, S., Khan, J.A., Habib, B. & Grassman, L. (2008). "Prionailurus bengalensis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T18146A7671433.http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T18146A7671433.en (accessed 10 November 2015).

Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S., & Ng, P. K. (2003). Catastrophic extinctions follow deforestation in Singapore. Nature, 424(6947), 420-426.

Miller, C. (2011). "Prionailurus bengalensis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web: http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Prionailurus_bengalensis/ (accessed 9 November 2015).

Izawa, M. (1991). Ecological study on the two species of Felidae in Japan. Wild-life Conservation, 141-143.

Lawrence, M. A., & Musser, G. G. (1990). Mammal holotypes in the American Museum of Natural History: the lectotype of Prionailurus bengalensis alleni Sody (1949). American Museum Novitates; no. 2973: http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/handle/2246/5068 (accessed 1 November 2015).

Ellerman, J.R., & Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Family Felidae, Order Carnivora. In Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 Second Edition. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/checklistofindia00elle Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 License. (accessed 1 November 2015).

Groves, C. P. (1997). Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 62: 330 pp.

Ellerman, J.R., & Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Family Felidae, Order Carnivora. In Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 Second Edition. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/checklistofindia00elle Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 License. (accessed 1 November 2015).

Izawa, M., Doi, T., Nakanishi, N., & Teranishi, A. (2009). Ecology and conservation of two endangered subspecies of the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) on Japanese islands. Biological Conservation, 142(9), 1884-1890.

Groves, C. P. (1997). Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 62: 330 pp.

Ellerman, J.R., & Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Family Felidae, Order Carnivora. In Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 Second Edition. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/checklistofindia00elle Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 License. (accessed 1 November 2015).

Masuda, R., & Yoshida, M. C. (1995). Two Japanese wildcats, the Tsushima cat and the Iriomote cat, show the same mitochondrial DNA lineage as the leopard cat Felis bengalensis. Zoological science, 12(5), 655-659.

Groves, C. P. (1997). Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 62: 330 pp.

Groves, C. P. (1997). Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 62: 330 pp.

Groves, C. P. (1997). Leopard-cats, Prionailurus bengalensis (Carnivora: Felidae) from Indonesia and the Philippines, with the description of two new species. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 62: 330 pp.

Ellerman, J.R., & Morrison-Scott, T. C. S. (1966). Family Felidae, Order Carnivora. In Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals 1758 to 1946 Second Edition. Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/checklistofindia00elle Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 License. (accessed 1 November 2015).

Miller, C. (2011). "Prionailurus bengalensis" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web: http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Prionailurus_bengalensis/ (accessed 9 November 2015).

Nowell, K., & Jackson, P. (eds.) (1996). Wild Cats: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN: http://www.iucn.org/about/work/programmes/species/publications/species_actions_plans/#mammals (accessed 1 November 2015).

Meachen-Samuels, J, & Van Valkenburgh, B. (2009). Craniodental indicators of prey size preference in the Felidae. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 96(4), 784-799.

Mohamed, A., Sollmann, R., Bernard, H., Ambu, L. N., Lagan, P., Mannan, S., ... & Wilting, A. (2013). Density and habitat use of the leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) in three commercial forest reserves in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. Journal of Mammalogy, 94(1), 82-89.

Rabinowitz, A. (1990). Notes on the behavior and movements of leopard cats, Felis bengalensis, in a dry tropical forest mosaic in Thailand. Biotropica, 397-403.

Kerr, R., & Gmelin, J. F. (1792). The Animal Kingdom Or Zoological System of the Celebrated Sir Charles Linnaeus: Class I. Mammalia (class II. the Birds): Containing a complete systematic Description, arrangement, and nomenclature, of all known species and varieties of the mammalia, or animals which give suck to their young. Being a Translation of that Part of the Systema Naturae. Edinburgh: Murray. Biodiversity Heritage Library: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/57940#/summary (accessed 9 November 2015).

https://scholar.google.com.sg/scholar?q=The+Tsushima+Leopard+Cat+%28Prionailurus+bengalensis+euptilura%29%3A+Population+Viability+Analysis+and+Conservation+Strategy&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5 (accessed 9 November 2015).

https://scholar.google.com.sg/scholar?q=The+Tsushima+Leopard+Cat+%28Prionailurus+bengalensis+euptilura%29%3A+Population+Viability+Analysis+and+Conservation+Strategy&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5 (accessed 9 November 2015).

http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/57940#/summary (accessed 9 November 2015).